Real-time Skepticism

or How I Became a Born-Again Skeptic

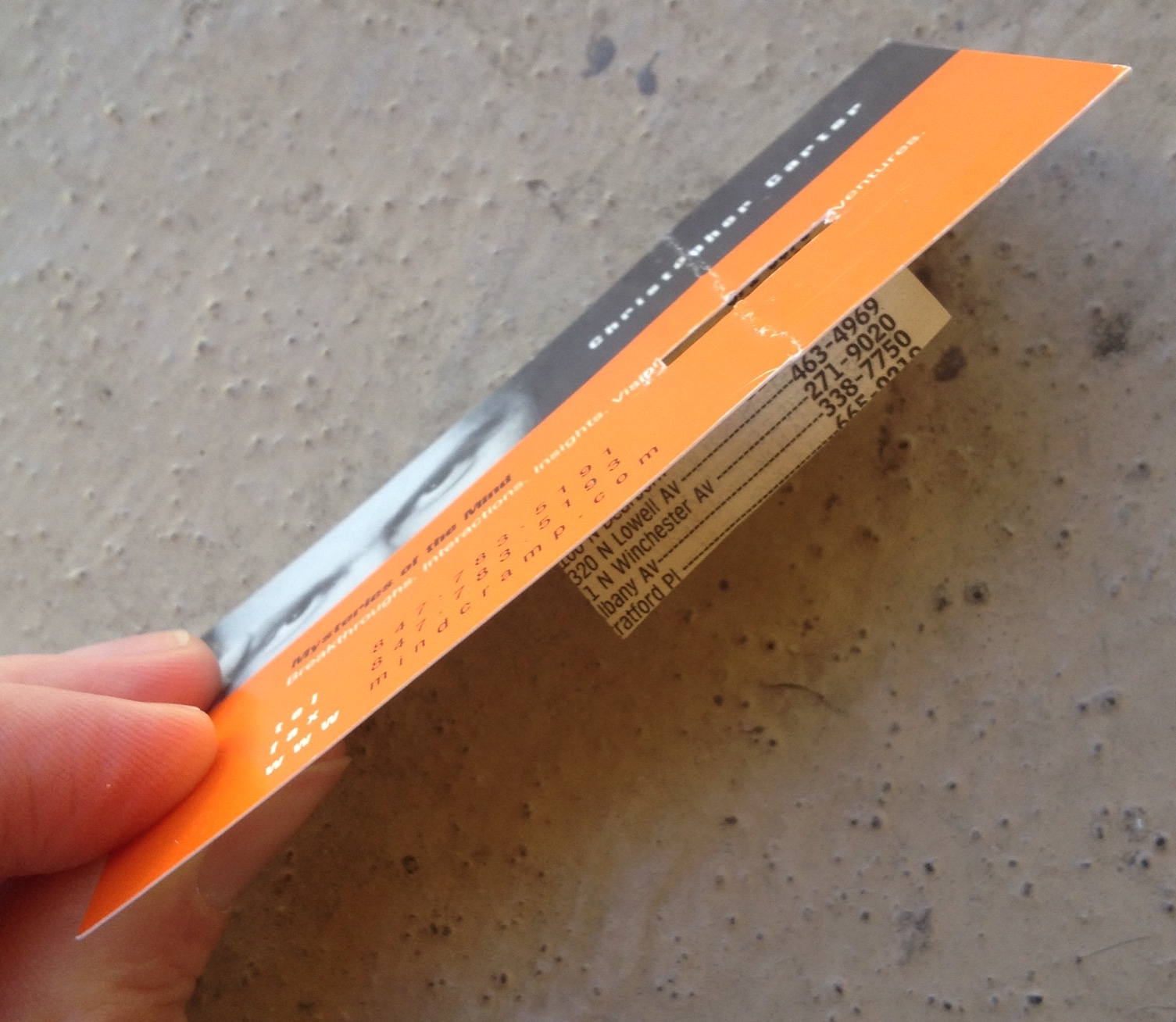

While we were cleaning out stacks of boxes and papers in 2015 in the corner of the apartment, my wife went through a box of old greeting cards and at the bottom she found this business card with a small cut out of phonebook paper taped to it.

I kept this around as a souvenir for a number of reasons.

But let us begin the story at the beginning.

In 2007 I was struggling with issues of identity and belief and authority and so forth. I took this all very seriously because for better or for worse people in positions of power lead large groups of vulnerable individuals to wrap up their beliefs and opinions with their identity because it is easier than accepting some of the cold, hard truths of our dispassionate universe, or admitting that those before you have all used the same shortcuts for generations and refused to admit not knowing something. Instead they made up the answers, for all of human history, until about the time of Galileo—but many groups since have not caught up. At this time I was in the process of unraveling my identity and my values.

Around this time I was also driving home from work every evening to eat dinner and spend time with my soon-to-be wife, still a student at the Caltech campus in Pasadena. One evening on campus there was a public performance at Ramo Auditorium of a magician who called himself a Mentalist and made annoying claims of paranormal and supernatural abilities.

Not everyone in the crowd was a Caltech student, alumni, or faculty but it was clear that there were many skeptical types of people in the audience. Throughout the evening and due to the anxiety of identity mentioned above and general anxiety in my life, my heart was pounding sort of trying to debunk the fellow’s stupid paranormal claims and to come up with simple explanations only involving standard trickery.

A lot of the tricks were easy to figure out and many of them involved suggestibility of various members of the audience, mathematical tricks, or broken assumptions. Throughout the performance his whole approach became more and more frustrating to me because he was essentially being deceptive but prattling on about mental powers in a very serious manner. In other words the problem wasn’t that he was deceiving the audience to entertain them, the problem was that he was deceiving the audience and claiming to have abilities which were based on the supposed bending of natural law.

(And lest we forget, some of the greatest magicians of all time, including the Great Randi and Harry Houdini, were some of the greatest skeptics and debunkers who ever lived. In addition, great stage magic is more impressive to skeptics because they actually do not believe in “real” magic and have a harder time with the fact that they have just witnessed the impossible.)

But skeptics as magicians generally wink and say they do their tricks by magic (they are up front that the phenomenon is “beyond reproach”) and leave it at that, whereas pseudoscience and paranormal proponents and mentalists first start by acting like their tricks are not tricks but can be subject to investigation, but when you look too closely they pull back in defense and then act like all of sudden the phenomena in question are beyond reproach. Which is it?

At the end of the evening the mentalist set up an elaborate trick which involved envelopes filled with single-digit numbers which he shuffled or pretended to shuffle in some order to spell out a telephone number, which he then produced by having a member of the audience open the telephone book to a random page where he would drag his business card with a window cut out of it (see the picture) across the page and stop at an arbitrary place determined by the audience member. I do not recall but perhaps he was even pretend blindfolded at this point. Now the audience member read out the phone number appearing in the window of the business card and then the envelopes were opened and it was revealed in a very showy manner that the digits matched.

During the applause and bowing and stage exit of the entertainer and with some excitement I rapidly worked through the steps of the trick and figured out that everything about it was very mundane except the only place to force that string of digits, already written in the envelopes, was the business card itself. I immediately ran down to the stage and picked up the business card off of the telephone book on the table and sure enough, using my skepticism and disbelief, I had worked through the only plausible solution to the illusion.

Another skeptic was wondering the same thing and even confronted me on stage to ask me if I was part of the act or defending the entertainer but I said, No, I had figured out the trick, and showed him the business card.

I was so full of adrenaline and excitement that I had won this little battle that I mostly inadvertently kept the business card. I meant the fellow no harm and I hope he went through all of his effects before going onstage later in his tour but I can assure you that he will not return to the California Institute of Technology. (I was not the only member of the audience giving him a hard time that night.) Luckily this piece of equipment is very inexpensive to replace.

He may have made suckers out of some people in the audience that night but he made a permanent disbeliever out of me. Using skepticism I had completely trumped this otherwise charismatic and convincing fellow, by simply questioning each assumption systematically.

Of course this was not the end of my internal journey but a beginning, giving a serious look at other groups that made similarly spectacular claims and appeal to emotion or appeal to authority with similarly shaky evidence.

I mean, not only was I a skeptic, I was a very good skeptic. (One would hope so as I had a job as an engineer debugging code all day and a four-year degree from one of the best science schools in the country.) Doubt had delivered the goods whereas faith (so-called) would have just rolled over and accepted it as beyond understanding.

By assuming there were no physical laws being broken and working the trick backwards my brain had determined the only solution to the problem.

(Of course like any magic trick, when you explain it, it kills the magic! In addition, pulling off a trick like this in front of an audience is obviously a lot harder than it sounds and takes years of practice.)